Return to Analog in the Digital Age

Written By Calvin Bailey.

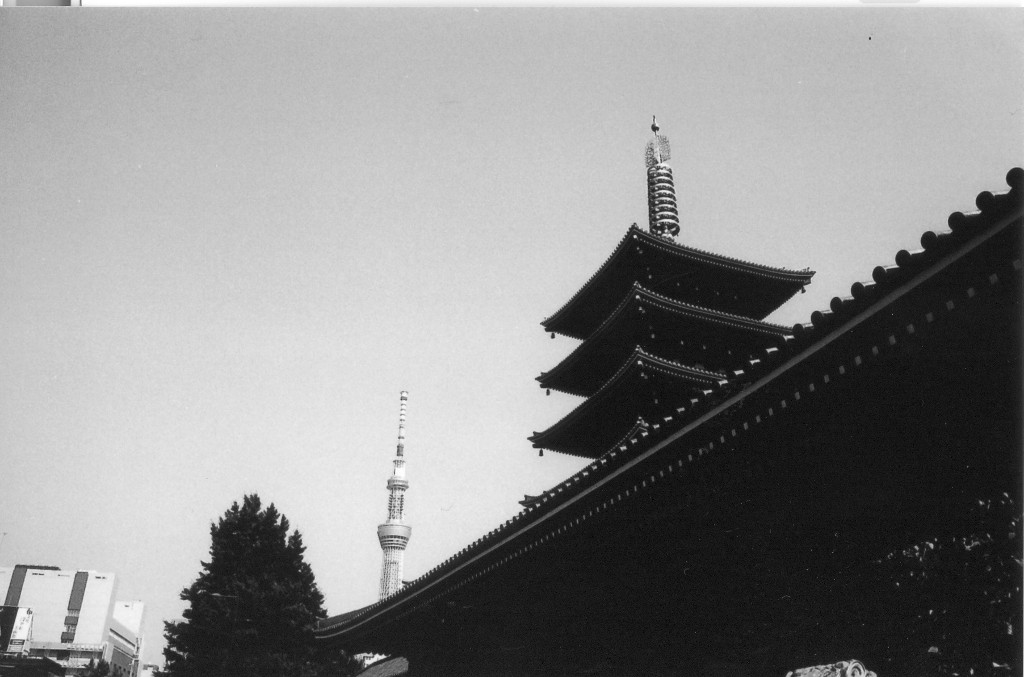

Film is on its way back. What exactly it is about film that makes me excited every time I load a new roll into my 35mm is hard to say, but I am not adverse to educated guesses. For me, and for many others, as I am inclined to believe, film exists on two different stages, which in some funny way complement each other. At one stage, film exists as a clear memory of trips to the chemist, index charts, family holidays, and as something gone by. Nostalgic as this interpretation of film is, one might argue that it is justified. I remember the excitement of being allowed to hold my mother’s Kodak (I forget the name of the model), and quickly snapping a few frames before my mother hastily assuring me that “those cost money”

At the second stage, film exists as a contemporary notion. This is to be understood as film being new and exciting in a way it never has been before. Of course, I would not imply that film is a new invention in the sense that it is not old. The point of defining film as new is simply to say that film truly is experiencing a renaissance. Although Kodak, one of photography’s best loved film companies has been discontinuing their production of some 35mm, as for example Plus-X - Lomochrome, Rollei, and last but not least Ilford, have steadily been presenting the market with new and exciting products. Film is exciting in the sense that we, in this very moment are able to influence its rebirth, and to some extent to be held reliable for its progress.

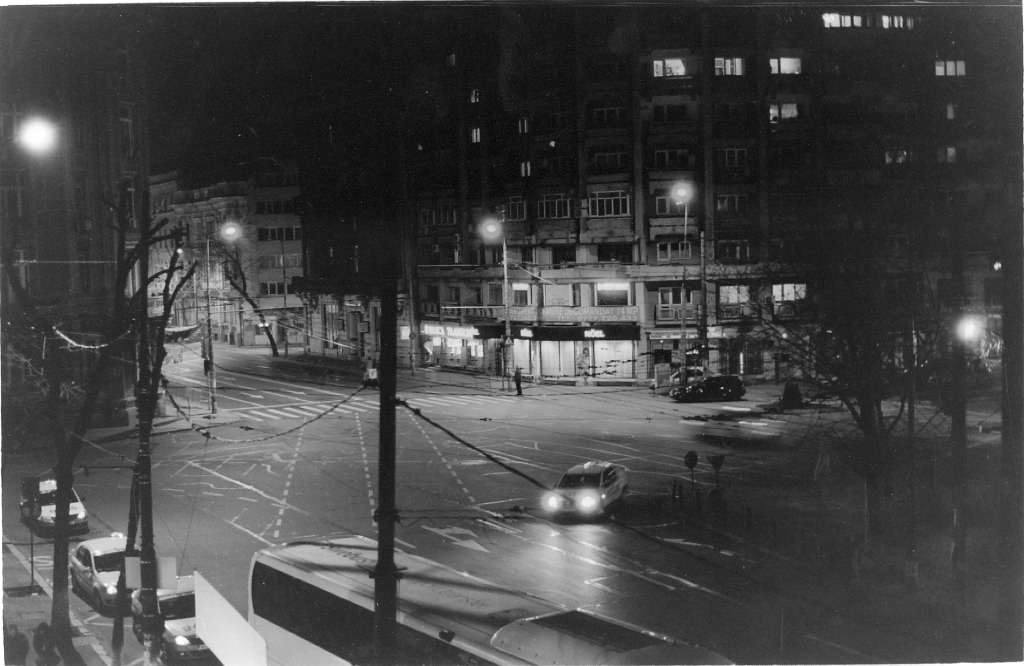

I am no stranger to modern technology – no sensible individual in the advanced world could claim to be – but I am impelled to make the point that my relationship toward my clever gadgets is not the same as toward the analog instruments I implement in the process of shooting film. Besides the possibility of some faint anthropomorphous rendition of technology I am myself not yet aware of, I relate no more to my smartphone than it does to me. To set a concrete example of this – I recall the time I dropped my phone. It could do anything; it had no limitations but speculated ones. As it fell to the hard pavement of a small town in northern Europe, screen shattering, naked circuit boards fleeing the scene of the crime, I could think nothing but: “Oh well…Shit.” To the contrary, my Minolta SRT 101 suffered an unrepairable shutter malfunction after a rather rigorous hiking trip. A mixture of a long life, former use by trendy photography students and other hardships had finally, after all these years, sucked the reliability from this Japanese crafted companion’s cold, steely grip.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the realization of this, without mercy thrust me back in time, making me remember the first time I had laid hands on it, the first time I had fogged the viewfinder with my breath and pressed my nose up against its fake leather backing. What is it that make me create these connections with an old piece of machinery? It could not have been the physical proximity to my person, as my smartphone had, figuratively speaking, been glued to the upper part of my thigh, resting in the left pocket of my tired jeans for an amount of time I do not care to elaborate upon. Yet it had not received a shred of the sort of attention I gave my Minolta, even though it had simultaneously been gathering global news and recommending quick and easy pasta recipes.

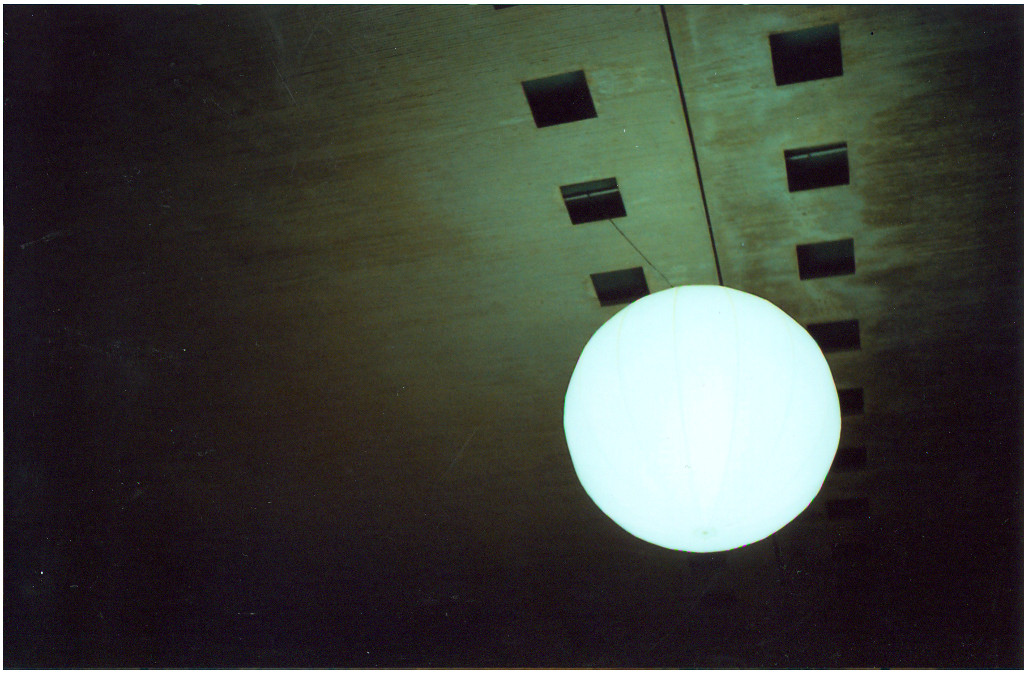

No, my affectation toward my Minolta simply must have been something else. We are living (whether we like it or not) in a state of liquid modernity, blended with a healthy dose of technocracy. Narcissistic tendencies are experiencing a blossoming, as the focus on the individual grows, enthralling the imaginations of a large part of the world’s population. Steadily, large parts of the world are abandoning traditional values, formerly upheld by institutions, (like the church) in light of realization of the power of the individual. In the digital age of flexibility, the analogue camera offers something strict, yet fair. Something unforgiving, yet manipulative. This, you can feel every time you wind the film, every time the shutter snaps, and you can finally breathe out.

No matter how much one would like to think that shooting film is no more than an artistic decision, it is naïve to ignore other aspects. Shooting film as an amateur photographer in the digital age is an image choice, (not to say that digital photography is not) although this choice is not necessarily a conscious one. For example in younger generations, shooting film has become somewhat of a pop-culture phenomenon, used by a part of the demographic that subscribe to a certain (sub)culture. The application of Goffman’s theory of frontstage/backstage tells us that our actions in the public eye are based in a need to portray ourselves positively. This is of course quite cynical, but thought provoking nonetheless.

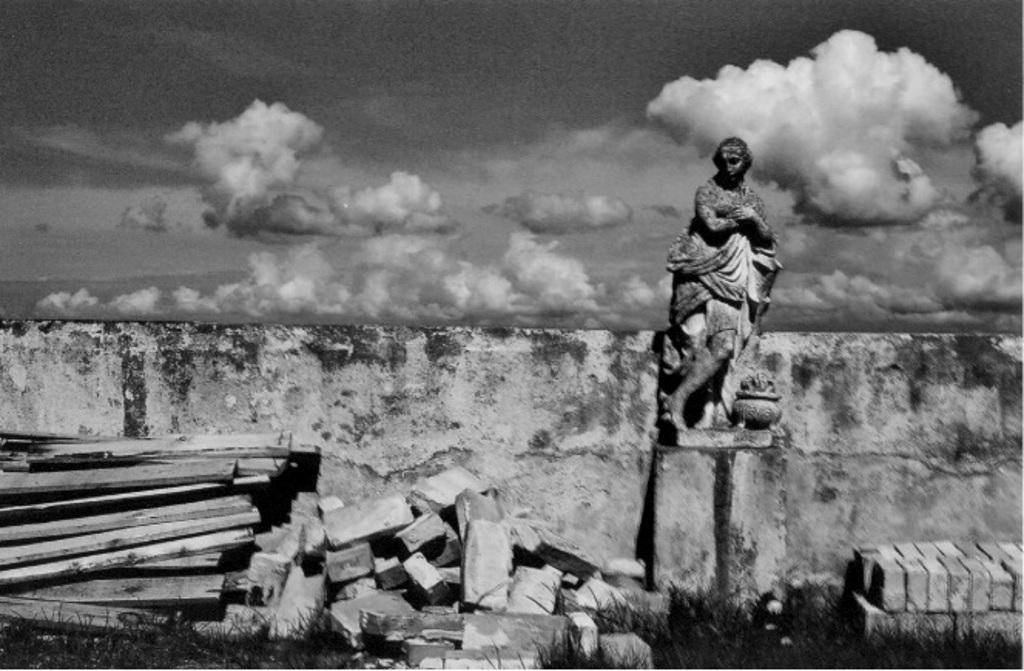

The fact of the matter is that newly forged appreciation of film and analog photography is not an isolated event of endearment of old technology. A new appreciation of the “vintage” and “old school” has been popularized in developed western countries. (I am quite sure that it is this self-same notion that makes me appreciate tweed, or at least causes me not to distain it, as one’s logical conclusion should be)

To say that all this devalues film photography in the digital age is a fallacy on all parameters. The love invested by any individual in the analog process enriches the world of film photography. Finally yet importantly, we have to share. Sharing pictures in the film photography community helps inspire others, and define the restrictions and challenges involved in the process, which eventually leads to a better understanding of why we shoot film.